What is PH? And what is PAH?

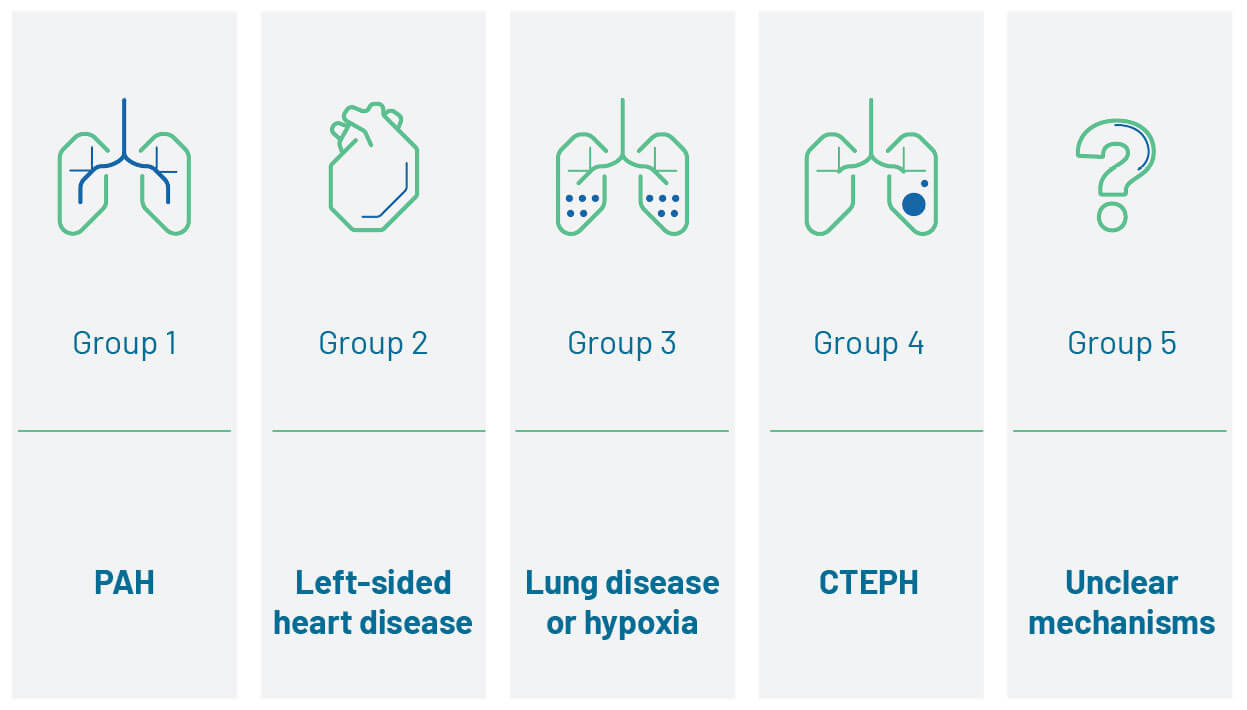

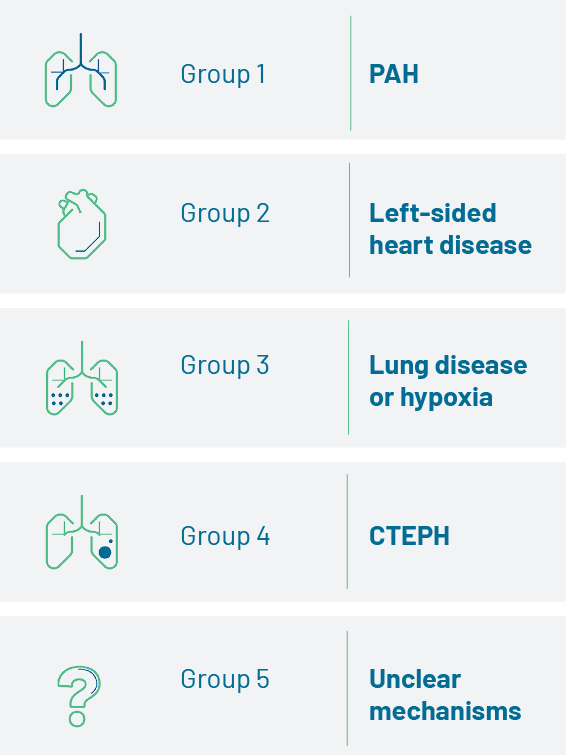

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a haemodynamic and pathophysiological disorder characterised by elevated blood pressure in the pulmonary arteries. It is found in multiple clinical conditions. Depending on the presentation, cause of the disease and haemodynamic definitions, PH is categorised into five groups:1

Symptoms of PH are non-specific, and mainly related to right ventricular dysfunction.1 They include symptoms like breathlessness that can be easily mistaken for other conditions such as asthma.1-4

As PH progresses, symptoms become more severe and begin to limit normal activities1

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

aThoracic compression syndromes are found in a minority of patients with PAH with pronounced dilation of the pulmonary artery, and may occur at any disease stage and even in patients with otherwise mild functional impairment.

Adapted from Humbert M et al. 2022.1

Symptoms such as unexplained breathlessness require investigation1

Patients with unexplained breathlessness, for which common causes have been excluded, could have PH and should have their symptoms investigated until a cause is found.5 Breathlessness that does not respond to COPD or asthma treatment after 4 weeks requires further investigation and may require referral to a PH expert centre.6–8

Differentiating PH and PAH

Early diagnosis and classification of the cause of PH are essential to tailor treatment strategy. Early diagnosis of PAH is crucial, with intervention at this point likely to delay disease progression and improve patient outcomes.1,3 If PH is suspected and the cause is unclear, early referral to a PH expert centre is important to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare but deadly form of PH. Unlike other forms of PH, the cause of PAH is mostly unknown.1

Key features of PAH

![]()

PAH is rare but deadly1,2

- PAH is caused by narrowing or blockage of pulmonary arteries.2,3

- PAH is one of five groups of PH.1

- 70–80% of PAH patients are female.9

- Mean age at diagnosis is between 50 and 65 years.9

Diagnosis is often delayed4,6

- Patients wait 2.5 years on average for a PAH diagnosis from the onset of symptoms.4,10

- PAH patients report an average of 5 GP visits and 2 specialist visits before being referred to a PH expert centre.4

Prognosis of untreated PAH is poor2

- Median survival can be as low as 6 months in patients who don’t receive treatment in time.*2

*Functional class IV patients who don’t receive PAH-specific treatment. - By the time PAH is definitively diagnosed, ≥50% of pulmonary circulation may already be compromised.11

Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial3

- Prompt referral to a PH expert centre for diagnosis allows patients to access crucial treatment early.1

- Early treatment may delay PAH progression and improve patient outcomes.1

WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENT SUBTYPES OF PAH?

![]()

PAH can be divided into sub-groups based on the underlying disease mechanisms:1

- iPAH – PAH with unknown cause (idiopathic); accounts for between 30% and 48% of all cases of PAH12

- HPAH – heritable PAH is often due to a specific mutation on the BMPR2 gene, but is sometimes due to other mutations; accounts for approximately 6–10% of cases of PAH13

- Drug- or toxin-induced PAH – may develop as a rare side effect of certain illicit drugs and toxins, such as methamphetamines and some chemotherapy agents1

- Associated PAH – PAH associated with other conditions, most commonly connective tissue disease (especially systemic sclerosis), congenital heart disease, HIV infection, portal hypertension, as well as other less common conditions1

Prognosis also varies between subtypes of PAH, for example the prognosis is generally worse in patients with PAH associated with connective-tissue disease (CTD), while patients with PAH associated congenital heart disease (CHD) usually have a better prognosis.9

How is PAH defined?

![]()

In healthy individuals, the mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) as measured by right heart catheterisation is 14±3.3 mmHg (mean±SD) at rest, with an upper limit of approximately 20 mmHg.14

PAH is a clinical condition characterised by the presence of elevated blood pressure in the pre-capillary pulmonary circulation (the pulmonary arteries and arterioles), without any other cause of pulmonary hypertension (PH), for example: due to lung disease, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, or other rare diseases.1

Specifically, the haemodynamic definition of PAH is as follows:1,14

- mPAP >20 mmHg

- PAWP ≤15 mmHg

- PVR >2 WU

What are the pathological changes associated with PAH?

![]()

Endothelial dysfunction, an abnormality of the inner lining of blood vessels, is believed to occur early in disease pathogenesis.15 This leads to endothelial and smooth muscle cell proliferation followed by structural changes, or remodelling, of the pulmonary vascular bed.15 Vascular remodelling results in an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), which is related to several progressive changes in the pulmonary arterioles, including:16

- Vasoconstriction

- Obstructive remodelling of the pulmonary blood vessel walls

- Inflammation

- In situ thrombosis

What are some of the clinical signs of PAH?

![]()

The increase in pulmonary arterial pressure (afterload) makes the right heart work harder, resulting in right ventricular hypertrophy, and leading to the typical symptoms of PAH.16 Initially, the heart is able to compensate for the increased pressure;15 however, as the disease progresses, the right ventricle (RV) becomes dilated, eventually resulting in a number of potential consequences:

- Right ventricular hypertrophy, which can, on occasion, reduce blood flow and lead to ischaemia of the right ventricle1,15

- Right heart failure, including all typical signs of systemic venous hypertension, whilst also occurring during a low cardiac output state. Syncope is a severe manifestation of right heart failure16

- Dyspnoea at progressively lower levels of exercise, eventually presenting at rest and often with frank syncope15,16

- Disability and death, occurring sooner if effective treatment plans are not initiated16

Footnotes

BMPR2: bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHD: congenital heart disease; CTD: connective tissue disease; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HPAH: heritable PAH; IPAH: idiopathic PAH; mPAP: mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; PAWP: pulmonary arterial wedge pressure; PH: pulmonary hypertension; PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance; SD: standard deviation; WSPH: World Symposium of Pulmonary Hypertension; WU: Wood units.

References

- Humbert M et al. Eur Heart J 2022;43(38):3618–3731.

- D’Alonzo GE et al. Ann Intern Med 1991;115(5):343–9.

- Bossone E et al. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2013;26(1):1–14.

- Strange G et al. Pulm Circ. 2013;3:89–94.

- Karnani NG et al. Am Fam Physician 2005;71:1529–37.

- Ferry OR et al. J Thorac Dis 2019;11(Suppl 17):S2117–28.

- Yang IA et al. COPD-X Concise Guide, 2019.

- National Asthma Council. Australian Asthma Handbook v2.1, September 2020.

- Hoeper MM. Gibbs JSR. Eur Respir Rev 2014;23:450–7.

- Khou V et al. Respirology 2020;25(8):863–71.

- Lau EMT et al. Eur Heart J 2011;32:2489–98.

- McGoon MD et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62(25 Suppl):D51-5.

- McLaughlin VV et al. J Am Coll Cadiol 2009;53:1573–61

- Simonneau G et al. Eur Respir J 2019;53(1):1801913

- McLaughlin VV et al. Circulation 2009;119:2250–94.

- Montani D et al. Orphanet Rare J Dis 2013;8:97.